- Home

- Lionel Bascom

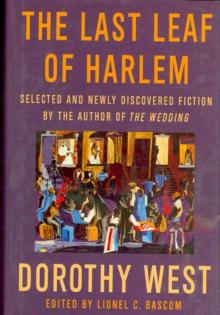

The Last Leaf of Harlem

The Last Leaf of Harlem Read online

Table of Contents

1.The Last Leaf: An Introduction

Autobiography

2.My Baby

3.No Room

4.Moscow

Part II

Early Fiction

5.Hannah Byde, Messenger -- 1926

6.The Typewriter, Opportunity July – 1926

7.The Funeral, Saturday Evening Quill, April, 1928

8.Prologue to Life, Saturday Evening Quill-April 1929

9.Cook, Challenge – March, 1934

10.The Five Dollar Bill, Challenge June 1936

Part III

The WPA Years

11.Ghosts, November 18, 1938

12.Pluto, November 28, 1938

13.Amateur Night in Harlem, December 1938

14.Temple of Grace, December 21, 1938

15.Cocktail Party, January, 1939

Part IV

Pulp Fiction

16.Jack in the Pot, September, 1940

17.The Penny, June 1941

18.Papa’s Place, 1941

19.Bessie, November 3, 1941

20.Mother Love, April, 1942

21.The Puppy, May 9, 1942

22.A Boy In the House, August 24, 1944

23.Cottagers and Mrs. Carmody, April 15, 1946

24.Skippy, April 29, 1946

25.A Matter of Money, May 15, 1946

26.Wives and Women, March, 1947

27.The Letters, August, 1947

28.Made for Each Other, August, 1947

29.Homecoming, April, 1957

30.Summer Setting, May, 1957

31.The Lean and the Plenty, March, 1957

32.Babe, July, 1957

33.The Richer, The Poorer, May 1958

34.Interlude, June, 1959

35.The Long Wait, November 2, 1959

36.The Birthday Party, April, 1960.

37.Mrs. Creel, June 1960

38.The Stairs, December, 1961

39.Bent Twig, March 1962

40.The Bird Like No Other, August, 1964

41.About A Woman Named Nancy, February, 1987

42.A Tale of Christmas and Love, December, 1979

Part VI

A Selected Literary Chronology

The Last Leaf

Taking a cue from a literary fixture of an earlier time, Dorothy West staked out a room of her own early in life where she could go to think and to write. This became a recurring theme for West throughout a long career as a writer of short fiction and journalism that began in her native Boston early in the 20th Century and lasted for more than seven decades. It was a lengthy adventure for a woman who was both an enigma of and significant contributor to the landscape of 20th Century American literature.

This collection is a literary rendering of her short fiction and journalistic stories, compiled just before and shortly after her death in 1998 and is an attempt to shed new light on an obscure and sometimes shadowy life of an important literary figure. The stories have been placed in this collection in the chronological order in which they were written, not in the date order that they were published since many of the works were never published.

Dorothy West lived the life of a writer, often carving out her fiction from the days and nights of her own life. Her writing life began with long, intimate pieces about her family in Boston where she was born on June 2, 1907. She was the only child of Isaac Christopher West, a freed slave who became a successful businessman who sold produce and Rachel Pease Benson, one of 22 children.

Throughout her life, West was a curiosity. As an only child, she was always surrounded by relatives, close and distant, who were taken in by her family. West never married, but changed her name several times during her career, using pseudonyms for her stories. Jane Isaac, one of her pseudonyms, was used on a story called Cook, which appears in this collection but was first published in a magazine called Challenge which was financed and published by West.

Her career was bookmarked by many essays about life in Boston, Harlem and the island of Martha’s Vineyard. Most of her work paints an idyllic portrait of life as Dorothy West saw it, but her work was also influenced by the racism and poverty that she saw and experienced as a black woman writer in America. Contrary to the image of her as the soft-spoken voice of old fashion ways and the gentle mores of the black middle class; Dorothy West could also sting as she does in Cook where she parodies her own kind as much as she chronicles their pettiness. West was always the observer and can often be seen as a social critic. She does this time and time again in stories like Cook, Jack in the Pot and many other pieces in this collection. Her short stories are laced with the moral twists, human drama and tragedy that marks all literature. Like her Russian mentor Fyodor Dostoyevsky, West aspired to create and recreate portraits of the human dilemma and she often succeeded in different ways and to different degrees, but her work is rarely credited for having this kind of edge.

Dorothy West was largely a short story writer, but she wrote two novels that both chronicled and satirized black middle-class and life on Martha’s Vineyard, where she lived for most of her life. The stories, sketches and remembrances in this volume were found over a period of years in widely scattered archives at colleges, universities and newspaper morgues I visited in Boston, New York and Washington, D.C. Her publishing credits began with the long short stories she published in Boston in the first two decades of the 20th Century. Her career ended with the brief sketches she was still writing at the end of her life for the Vineyard Gazette, the newspaper that had published her work for more than fifty years.

One of the persistent criticisms of her work is that is was spotty with long, dark periods of inactivity. This does not appear to be wholly true. Dorothy West was never totally silent, despite claims that she had long periods when she did not write. All writers experience slow periods. Their work won’t sell, is too difficult to publish or sometimes impossible to finish, to sell or publish.

In Pentimento, the acclaimed autobiography of playwright Lillian Hellman, readers are treated to an uneven but realistic journey through a writer’s life that is often as it was fulfilling, exhausting and sometimes iconic. The writing life Dorothy West lived was apparently no easier than Hellman’s. Her writing life was sometimes interrupted by bouts of difficulty, and of financial, political and personal woes, according to people who were close to her. A Connecticut lawyer, who represented heirs of her estate, for example, told me that West worked many odd jobs to feed herself during financially lean years of her life. We generally view creative artists in retrospect, seeing them almost exclusively on the high perches where we’ve placed their greatest works. But this robs us of the rare opportunity to witness their climb to greatness and skews our view of both the art and its creator.

This book is not intended to double as a critique of West or her work. I am not in the literary criticism business. I like to call myself a literary journalist, a self-styled literary anthropologist who tells stories by adding new flesh to the old bones of literary biography.

Dorothy West wrote fiction for newspapers throughout a career that may have started as early as 1915. Her first stories appeared in the Boston Post and her last stories were published posthumously in the Vineyard Gazette and the New York Daily News in the late 1990s after she died. A story she wrote in the late 1930s, My Baby, while a writer for the Work Progress Administration in the New York Writer’s Project, was not published until the year 2000 after I found it in the Library of Congress. It was first published in Connecticut Review; and subsequently republished in America’s Best Short Stories, 2001, edited by Barbara Kingsolver.

As you will see, this collection contains a wide range of her short fiction, most of it written for daily newspapers. This fact alone does no

t render the work inferior, although some have argued with me that it does. Critics have called West “a second rate journalist,” As a writer and journalist, I believe that some of the best American fiction and prose were first published in newspapers. In fact, it is a much-maligned, and ignored literary genre that more literary critics should study.

Much of the great literature of modern times was first published in newspapers like the Times of London, the New York Times and the New York Daily News. In fact, the News and the Times ran regular sections containing short fiction into the 20th Century, only ending the practice in the early 1960s. So, to have published her fiction in a newspaper puts West in the company of such giants as Charles Dickens, Stephen Crane, Ernest Hemingway and many others. This means Dorothy West was among the last surviving members of a very large group of notable writers who also launched their literary careers by first publishing their fiction in newspapers.

Her work can also be placed in the same canon with thousands of unknowns who together created a widely popular genre of literature called pulp fiction. The plots in pulp fiction are usually anchored in the daily lives of relatively ordinary people, much like the plots of opera and most Shakespearean dramas. The stories in this collection are ordinary in this way too.

No work is created in a vacuum, so the circumstances under which this work was created (for money, influenced by prevailing political winds, etc.) are factors that need consideration too. Although much of this type of work appeared in newspapers, it is not journalism. It is pulp fiction intended for the working class readers who paid a nickel or dime to be entertained. The stories were not meant to be literature, no more than the pulp fiction of Dickens, Crane or Hemingway. Dorothy West belongs to this literary club. Her membership in it began with the fiction she sold and published in short story contests sponsored by the Boston Post during or shortly after World War I. It was still common then to see fiction and poetry in the same columns where crime and society news were printed. This fact will disappoint some and taint her work and career in some critics’ eyes. This is inevitable.

There are many surprises imbedded in the content of West’s stories. Most of the characters she created, for newspaper readers in the 1940s and in later decades, were white. This fact hurls West into the center of a long-standing controversy. In American literary circles, it has never been accepted that black authors could write freely and accurately about white communities or characters. West was called the chronicler of the black middle class, but she created many characters who were presumed to be white.

Who gave Dorothy West permission to step out of her assigned role as a black woman writer? Certainly not the same folks who gave William Faulkner, George Gershwin, Dubose Heyward, William Brashler and Joel Chandler permission to write about black folks and other cultures not their own. Faulkner certainly knew and could write well about southern blacks. Gershwin and Heyward successfully captured the character of Gullah culture down south in Porgy and Bess. Brashler, a Chicago writer, was often criticized in the 1970s for trampling on the territory black writers saw as their own. The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings is Brashler’s novel about the Negro baseball leagues. Chandler, the southern journalist from Atlanta, was the 19th Century chronicler of black folktales in the Uncle Remus stories.

Dorothy West joins these folks in this sensitive sub-genre, but from the other side of the color line. She made no apologies for this, so I make none in this collection either. None is necessary. This fact merely illustrates a more important idea, the fact that Dorothy West was an innovator at a time when America was a segregated nation where blacks and whites did not intermingle anywhere in public.

Dorothy West wrote most of her pulp fiction between the year 1940 and well in to the 1960s. Her stories were syndicated in some of the largest circulation newspapers in America, including the New York Daily News when the newspaper had a daily circulation of more than two million readers.

The work in this collection spans decades, years that were noticeably glossed over in some of the literary criticism I have read about West. Those same years and many more of her accomplishments are correctly noted in a general library reference work called Contemporary Authors. In it, I found a hint about the real legacy of Dorothy West, buried between the lines of a small blurb about her career. “Critics and aficionados hope to read more of her creations, many of which remain unpublished,” it said.

The sheer number of stories she wrote refutes the widely held claim that the years between her two novels, 1948 and 1995 were silent. Dorothy West was rarely idle as a writer during her long life.

Dorothy West was no fool. A graduate of the prestigious Latin Girls School in Boston West grew up in black Boston. She grew into a woman who knew the sting of racism in America although her work didn’t always reflect a direct awareness of it.

West wrote protest literature against racism, sexism and the other social ills that befell America after World I, during the economic depression and the world war, which followed in the 1940s. Dorothy West was a social critic, but protest literature written by blacks in the early part of the 20th century and, even in the succeeding decades, did not sell and West was trying to establish herself as a writer. As the daughter of a former slave she had to know the realities and the consequences of being black in America. She was no fool when it came to knowing what stories would sell and what would not. Protest literature would fail for an aspiring black woman trying to sell short stories to white publishers.

The themes West chose to write about generally focused on social or moral issues. This does not mean she never wrote about race, but she was a pragmatist who used satire, subtle shadings and outright subterfuge to deliver narratives that tackled difficult issues like race prejudices or the oppression of women in America. Neither of these subjects were areas publishers were willing to pay a black woman or a woman of any color to write. Yet, Dorothy West started a writing career in the early 1920s and sustained it for the next seventy years. This sometimes took courage and a great deal of cunning and Dorothy West, it seems, had both.

Whether tending to the needs of the many relatives, who drifted in and out of her life as a girl in Boston or working as a welfare investigator in Harlem, West was a writer first. When she joined a federal work project in the late 1930s or when she worked as a restaurant cashier, Dorothy West was a writer in the act of gathering material for her next book or story first.

Her fiction generally mirrored her surroundings and her stories are filled with the people who were involved in her life. Hers was a life that seemed to always coexist with her stories, sometimes making it difficult for an outsider like me to distinguish facts about her life from the fictions in it. Such is the life of a writer’s writer. Dorothy West lived and worked inside of her muse, not side by side with it. The two were enmeshed into a kind of literary soup. This was a contemplation which she began early in her life as a teenager that later made the fact and fictions of her life inseparable.

As self-styled, literary anthropologists, I first became acquainted with Dorothy West through a happy accident. In researching another collection of stories I was doing about the Harlem Renaissance era, I knew that West was a legendary black writer from that time. The Harlem Renaissance began in the mid 1920s when an unprecedented number of literary figures gathered in this all black section of Manhattan and began to publish a wide assortment of novels, short stories and essays. It was during this research in the early 1990s that I first found and began to admire her odd, old fashion writing style. My interest in her work was heightened when I found several unpublished stories she had written in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress in Washington. It was mingled among the work of others, including such well known writers as Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man, and Zora Neale Hurston, author of Their Eyes Were Watching God.

The first story that impressed me is called Pluto, a non-fiction title taken from the dog character in the Walt Disney cartoon Mickey Mouse. In this first-pe

rson narrative, Dorothy West is disturbed one morning in her Harlem apartment by an unexpected knock on her door. What follows is a precise, chilling social commentary by West about hunger and poverty during the Depression years in America and her own initial indifference to it. The piece is both subtle and piercing. It is so carefully crafted, it teeters on that precarious border where fact does meet fiction and the two collide in your mind.

Pluto was written in the late 1930s when West worked as a $20-a-week-writer for the Work Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Writer’s Project. It had never been published and I immediately wondered why.

To my amazement, there were at least a half dozen other stories by West in this same archive that had never been published. These stories were part of a larger cache of narratives from the Federal Writer’s. The stories had been edited and earmarked for publication but most of them never made it into print.

The Work Progress Administration was a make-work federal project more commonly known as the WPA that was abruptly disbanded around 1940 when the Depression ended. When it closed down, thousands of manuscripts, like the ones I found, were shelved and forgotten for decades.

Other work by West had been published throughout her career but much of it was equally obscure for different reasons. Many of the stories she wrote were buried in old archives that had never been indexed. I found some of it carefully indexed but still buried deep in the literary collections of other writers like Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson and others at libraries at Yale, Boston University and the Schomburg Center of Black Culture in Harlem. This is how I found pieces of her work in libraries up and down the Atlantic coast, each with a similar story attached to it.

In the hushed surroundings of these libraries and archives, I found manuscripts, old newspapers clippings and pieces West wrote that were published under at least two different pen names. This work was certainly prized by librarians whose job it was to take care of old manuscripts like those I was finding. But, the ideas, sketches and stories by this now aging woman who was still alive then and in her late 80s, had been obscured by years of neglect, time and unusual circumstances.

The Last Leaf of Harlem

The Last Leaf of Harlem