- Home

- Lionel Bascom

The Last Leaf of Harlem Page 2

The Last Leaf of Harlem Read online

Page 2

Ironically, Dorothy West was enjoying a renaissance of her own about the same time. Her name and reputation were being resurrected in wider literary circles and important literary scholars and popular critics were again feting her life and her work.

This renewed attention meant that Dorothy West had lived long enough to become a literary enigma in her own time. She was famous and obscure at the same time.

Time magazine, for example, said she was enjoying a second round of well-deserved fame with publication of her second novel, The Wedding, in 1995. Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, then an editor for Doubleday books, had discovered West living on Martha’s Vineyard where West still wrote for the Vineyard Gazette. Onassis’s decision to publish the first novel West had written in almost fifty years was cause for some celebration. Her first novel, The Living Is Easy (1948), had already been republished by The Feminist Press in 1982 and was still in print.

Although she always saw herself as more of a short story writer than a novelist, she was most famous for the two novels. The five decades between the years 1948 and 1995 are the years that critics claim Dorothy West appeared to have stopped writing.

This long standing claim is fiction.

Dorothy West was prolific.

The career they were celebrating began when she routinely began to win short story contests sponsored by the Boston Post. She was also a regular contributor to Saturday Evening Quill, a small Boston literary magazine which published stories of local writers.

Her career was broadened around 1924 when she won a literary prize for “The Typewriter.” Opportunity, the New York-based magazine started by the National Urban League, had chosen the story and invited West to New York to pick up her cash prize. When she arrived, she joined a loosely formed network of Negro writers in Harlem who collectively became known as the Harlem Renaissance writers.

A decade later, West joined the New York Writer’s Project of the WPA. In the 1930s, she founded a literary magazine called Challenge. It was later renamed New Challenge and West co-edited it with writer Richard Wright, who came to New York from the south by way of Chicago.

In the limited circles of black Boston and in Harlem, Dorothy West had become famous by the end of the 1930s.

By the start of the next decade, her work caught the attention of literary agent George T. Bye, a high-powered figure in New York publishing circles. Bye represented First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Rebecca West, Katherine Ann Porter, and many other important writers of the period. In a lucrative deal, he negotiated for West to write regularly for the New York Daily News. She began a long-term relationship with the News to write short stories for the Blue Ribbon Fiction section of the paper. Laid out in the comic strip section, Blue Ribbon Fiction stories often ran on a page anchored by the popular Terry and the Pirates comic strip. For the next twenty years between 1940 and the early 1960s, the name Dorothy West appeared over more than forty short stories.

The first story she wrote depicted the life of a black couple in a Harlem tenement during the lean years of the Depression. It was called Jack in the Pot.

“They liked Jack in the Pot, the one and only black story (of mine) they printed,” West said in an interview. “I wrote it for a contest (at a magazine). The magazine forwarded it to them for their Blue Ribbon Fiction,” West said in an interview she gave in 1978 for the Black Women Oral History Project at Radcliffe College. “I had to cut it. I learned a great deal at the News. I learned to cut,” West said.

“All my friends were so contemptuous that I was writing for the News,” she said. “It was keeping me eating. I got four hundred dollars.” She said friends attributed the high fee she was paid to the fact that she had Bye as her literary agent.

“George Bye had me in his stable. He had Eleanor Roosevelt and a lot of famous people. I got him through Fannie Hurst. Zora Neale Hurston introduced me to Fannie Hurst,” West said.

Ironically, while West was represented by an agent whose clients were famous, her fame and her work began to slip into obscurity though she was now producing stories that were being read by millions of newspaper readers. The News alone had a daily circulation of well over 1.3 million readers. After Jack in the Pot appeared, the stories she wrote over the next twenty years were distributed to numerous other newspapers throughout the world by the News Syndicate, Inc., making Dorothy West one of the most widely read black writers in America at the time. Since her characters weren’t black, and she wasn’t identified as a black writer, few people knew these facts about her stories or her career.

This situation is ironic for several reasons. At a time when her fame and notoriety should have soared because of this relationship with Bye and the News, it plummeted instead. She fell from view of critics who either did not know she was now a regular contributor to the News or the fact that West, a black writer was regularly writing stories with an all white cast, became a subject that was taboo to them. In either case, her career as a short story writer fell prey to rumors that Dorothy West had retired. This claim remained a fixture in the literary biographies written about her throughout the rest of her life.

So, while West was writing for a syndicate that distributed her fiction to newspapers throughout the world, this became a shadowy time in her life.

The News was distributed on newsstands throughout the many white, working class neighborhoods of New York City. Many readers were white immigrant women, whose lives were far removed from the realities that most often confront black Americans. In order to be published here, West seemed to have no choice but to invent white characters her readers could relate to.

This begins a significant chapter in West’s literary career. Dorothy West became what author Robert A. Bone called an assimilationist.

West was developing as writer in the late 1920s when she met Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Frank Yerby and other fledgling artists in Harlem. In the early days of the Renaissance years in Harlem, these black writers enjoyed being published in the mostly black, little magazines that sprang up solely to publish their work. In the years between 1920 and the late 1930’s, the fiction of Harlem writers like West appeared in The Crisis, the NAACP magazine, Opportunity, the Urban League magazine and in Challenge and later New Challenge.

About the same time, Hurston, Hughes and others were published in Fire!!, a single issue, literary magazine its founders said, “was intended to burn up a lot of the old, dead, conventional Negro ideas of the past.” The political writings of other Harlem writers found an outlet in a socialist magazine called The Messenger, edited by A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, who founded this radical weekly.

The plight of black life in America was regularly laid bare in these magazines. But by the 1940’s, almost all of these magazines except The Crisis had folded, leaving black short story writers like West with almost no place to publish their stories.

“A good index to the general temper of the period is the lack of any center of gravity for a specifically Negro art,” Bone says in his book, The Negro Novel in America. “There are no little magazines in the forties and fifties to perform the function of Fire and Harlem during the Renaissance, or of Challenge and New Challenge during the Depression.” So there was no cohesive movement in contemporary black literature, Bone said, which led writers like West, Yerby and even the acerbic Hurston to become what he called assimilationist writers.

“On the whole,” Bone said in examining the period, “the young writers have preferred to seek non-racial outlets for their work. In doing so, these writers were abandoning the assertively racial fiction pioneered by Wright in novels like Native Son.”

Assimilationist turned to commercial fiction, which meant abandoning racial themes and in most cases, black characters and all black communities altogether. In the years between 1945 and the early 1950’s, some thirty-three novels by black authors were published. Thirteen, or more than a third of these, had predominantly or all white characters. Among the most notable writers of this genre were Frank Y

erby, Hurston, and Ann Petry.

Yerby, who had published stories in Challenge too, had also worked with West and Ellison on the staff of the New York Writer’s project of the WPA. According to Bone, Yerby had been a race conscious southerner during his early years in New York too. By the mid 1940s, he was still writing protest stories, but by the early 1950s, Yerby had moved to Spain and began to write wildly popular romantic, potboilers that featured mostly white plots and white characters. Others followed this path too.

Chester Himes wrote Cast the First Stone in 1952. Willard Motley wrote Knock on Any Door in 1947 and We Fished All Night in 1951. All are novels with raceless characters. In 1948, Hurston wrote Seraph on the Suwanee, a novel in set in the rural south in which she abandons black characters and the folk culture for which she would later become most famous. A year earlier, Connecticut born writer Ann Petry, known for her protest Harlem novel, The Street, published Country Place. This story of dying values is set in New England, presumably patterned after Petry’s mostly white hometown of Old Saybrook, Connecticut.

All of these writers became assimilationists and continued striving to break into the arena of mainstream publishing.

Dorothy West joined this group when she began writing for the News. She said it was a stipulation that was made implicit in her agreement with News’ editors who agreed to publish her stories if she complied. Rather than showing us people with unusual character, who also happened to be black, West repeatedly delivered stories with ironic twists aimed at the hearts and minds of readers who were mostly working-class whites. These characters sometimes lack the magnetic substances, which endear us to tragic black figures like Cleo, the scheming protagonist in one of West’s two novels, but this does not prevent me from feeling some empathy or pity for Bessie, a scheming hag in one of West’s short stories in this collection who happens to be white. Her race is not as important as the fact that she is snared by her own plot to control the people she claims to love.

This is the kind of story West wrote throughout this period, churning out numerous pieces of short in this way. Simultaneously, these same stories were syndicated by the News Syndicate, Inc. and in turn, were read by tens of millions of newspaper readers throughout the country and possibly the world. This made West one of the most widely read writers from the Harlem Renaissance period, and not just the youngest member of the elite group.

Sadly her work was never indexed, so it disappeared from public view only days after it was published with little or no easy way to retrieve it weeks, months or years later. Other work by West disappeared because it was written under the pen names she used. West said she generally used two, Mary Christopher and Jane Isaac. A third name, Mildred Wirt, has been attributed to West but she denied ever having used it.

Mildred Wirt, it turns out, is the name of a real writer, who was born about the same time as Dorothy West. Wirt was one of the many writers for the famous Nancy Drew mystery series. A source who knew Wirt, told me that the real Wirt once used the name Dorothy West as her pseudonym for a children’s book she wrote that was called Dot and Dash.

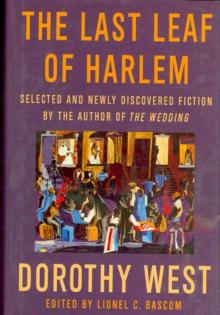

Shortly before she died in August of 1998, West told an interviewer for the New York Times Book Review that she was the last leaf on a now famous tree of black authors from Harlem. West, of course, was talking about her place among the black intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance. This lasting image of Dorothy West as the kid sister to Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes and Claude McKay does not reflect her unusual vigor as a short story writer and novelist.

Dorothy West was probably the youngest writer identified with the Harlem Renaissance, but she was also probably the most widely published and read author of the period, credit she has never been given in life or death. Paying this tribute to her now in no way diminishes the notable achievements of important writers like Ellison, Hurston, Hughes and the others from her days in Harlem, it merely reflects her role more accurately.

When the Renaissance years ended in the early 1930s, West stayed in Harlem for a few years. She founded Challenge, traveled to Russia to make a film, and traveled in a road show of Porgy and Bess as an actress. When a relative fell ill on Martha’s Vineyard in 1940, Dorothy West left New York and never returned.

In the succeeding years, she would write just two novels, with decades between them. This fact she would be chided with throughout her life. Without access to the pundits who had been charmed by her early work and presence in New York, the name Dorothy West faded from public view.

West did seem like a fallen literary figure of the Harlem Renaissance. Her creative flame appeared to flicker briefly in the 1920s, then go out. This tragic story about the premature end of a promising literary career seemed to be true. As romantic as these notions seem, they aren’t wholly true.

When Dorothy West died, these notions of a short-lived literary career appeared in the obituaries and eulogies published about her. Journalists failed in almost every way to document the rich literary legacy that Dorothy West left for us to ponder.

I came by this conclusion gradually as I found more and more of her work. The fact that this work existed and I was finding it wasn’t the nature of my true discovery. I knew that various scholars in different locations and disciplines knew about these obscure stories and some had read them.

A librarian at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem clarified the significance of what I was really seeing – the obscured work of a writer. The work of Dorothy West had never been thoroughly indexed, making a comprehensive collection of it difficult, if not impossible, to compile, the librarian told me.

After thorough searches at the Library of Congress and other libraries this omission became the center of my real discovery. I zeroed in on the stories which had been published by the News and have compiled them for the first time into this collection. This is what makes this collection significant.

Librarians at the News did the hard work of helping me find the probable dates of nearly twenty of these stories. It took them months of searching. Pearlie Peters, a professor in the English Department at Rider University in New Jersey, offered me a list of nearly twenty other stories she had located from sources in Boston. Together, we have located more than forty stories that others can now read in one source.

For many reasons that I have detailed, Dorothy West became invisible after she left New York. This was an almost terminal condition which her Harlem contemporary, Ralph Ellison, first identified in his novel, Invisible Man, and explored repeatedly during his lifetime.

Ironically, the era which made both West and Ellison famous seemed to suffer the same fate. Harlem itself became an invisible, no-man’s land after 1929 when worsening economic conditions dried up the loose life which had brought white tourists to Harlem in droves. Standard history books claim the Harlem Renaissance ended abruptly despite the fact that West, Ellison, and Zora Neale Hurston all published landmark novels years later.

Like the unnamed character in Ralph Ellison’s novel, Dorothy West had gone underground and remained there until Skip Gates from Harvard and Jackie Onassis found her again living on Martha’s Vineyard. But as West told an interviewer for Ms. Magazine in 1995, just because she had left New York and was no longer in the limelight that had once illuminated her career, “didn’t mean I had stopped writing.”

In a tribute following her death, the Vineyard Gazette reprinted some of the columns she had written for that newspaper. It was in these columns that West essentially wrote and serialized her personal history over a fifty-year period.

In one of the columns, West tells the story of how she began writing at the age of seven.

“When I was little, I asked my mother if I could go to my room.”

“‘Yes,’ my mother said, ‘but why do you want to go to your room’”

“‘To think,’ I told her.’”

“I went to my mother again later. This time, I asked if I could go to my room and lock the door.”

“‘Yes,’ m

y mother said, ‘but why do you want to lock the door?’”

‘Because I want to write,’ I told her.

Over the next century, that room was sometimes in a fashionable section of Boston and at others in a tenement building on 110th Street in Harlem where she lived and wrote stories about depression-era poverty and the black people who survived it. Later in her life Dorothy West wrote from the two-bedroom cottage her father had built for family retreats in a wooded section on Martha’s Vineyard. Throughout her long life, Dorothy West seemed to always have a room of her own in which to think and write in tranquility behind a closed or locked door.

So, I can think of no better way to acquaint you with that life and this work than by pausing here to let you read what Dorothy West had to say about herself. Her own words invite us inside the world of an important 20th Century writer’s life.

Autobiography

MY BABY …

One day during my tenth year, a long time ago in Boston, I came home from school, let myself in the back yard. I stopped a moment to scowl at the tall sunflowers which sprang up yearly despite my dislike of the, and to smile at the tender pansies and marigolds and morning-glories which father set out in little plots every spring, and went on into the kitchen.

The back gate and back door were always left open for us children, and the last one in was supposed to lock them. But since the last dawdler home from school had no way of knowing she was the last until she was inside, it was always mother who locked them at first dark, and she would stand and look up at the evening stars. She seemed to like this moment of being alone, away from the noise in the house.

We were a big house. Beside the ten rooms, and the big white-walled attic, there were we three little girls and the big people, as we used to call them.

The Last Leaf of Harlem

The Last Leaf of Harlem