- Home

- Lionel Bascom

The Last Leaf of Harlem Page 5

The Last Leaf of Harlem Read online

Page 5

He fumbled, “No, no, hon. You’re jes’ nervous. I know you women. Jes’you set down. I’ll go see if Doc’s home.”

She gave a deep sigh. Habitual apathy dulled her tone. “Please don’t bother. I’m all right. It’s nerves, I guess. Sometimes the emptiness of my life frightens me.”

A slow anger crept over him. His lips seemed to thicken. “Look here, Hannah. I’m ‘tiahed of your foolishness. There’s limits to what a man will stand. Guess I give you ev’rything anybody else’s got. You never have nothing much to do here. Y’got a phonygraph-and all them new records. Y’got a piano. I give you money las’ week to buy a new dress. And yisterday y’got new shoes. I ain’t no millionaire, Hannah. Ain’t no man livin’ c’n do better’n his best.”

She made a restless, weary little gesture. She began to loathe him. She felt an almost I insane desire to hurt him deeply, cruelly. She was like a taunting mother goading her child to tears.

“Of course I appreciate your sacrifice.” Her voice shook a little with hysteria. “You’re being perfectly splendid. You feed me. You clothe me. You’ve bought me a Player Piano which I loathe-flaunting emblem of middle-class existence - Oh, don’t go to the trouble of trying to understand that--And a stupid victrola stocked with the dreadful noises of your incomparable Mamie Waters. Oh, I’m a happy, contented woman! ‘There never is anything to do here.’ “She mocked in a shrill, choked voice. “Why, what in God’s name is there to do in a dark, badly furnished, four-room flat? Oh, if I weren’t such a cowardly fool, I’d find a way out of all this!”

The look of a dangerous, savage beast dominated his face. He stood, ill this moment, revealed. Every vestige of civilization had fled. One saw then the flatness of his close-cropped head, the thick, bull-like shortness of his neck, the heavy nose spreading now in a fierce gust of Uncontrollable anger, the beads of perspiration that had sprung out on his upper lip, one wondered then how the gentle woman Hannah could have married him. She shut her eyes against his brutal coarseness, his unredeemed ignorance – here no occasional, illiterate appreciation of the beautiful – his lack of spiritual needs, his bodily wants. And yet one sees them daily, these sensitive spiritless Negro women caught fast in the tentacles of awful despair. It seems almost as if they shut their eyes and make a blind plunge, inevitably to be sucked down, down into the depths of dreadful existence.

He started toward her, and she watched his approach with controlled interest. She had long ago ceased to fear his anger and had learned to whip him out of a mood with a flick of her scathing tongue. And now she waited unmoving for the miracle of his heavy hand to end her weary life.

His eyes were black with rage. “By God you drive me mad! If I was any less of a man I’d beat you till you ran blood. I must have been crazy to marry you. You, you!

There was a sharp rapping at the door, drowning his crazy words. Hannah smiled faintly, almost compassionately.

“The psychological moment. What a pity. George.”

She crossed the floor, staggering for an instant with a sudden, sharp pain. She opened the door and unconsciously caught her lip in vexation as she admitted her visitor.

“Do come in,” she said, almost dryly,

Tillie entered. Tillie, the very recent, very pretty, very silly wife of Doctor Hill, a newly wed, popular girl finding matrimony just a big cramping.

She entered boldly, anticipating and ignoring the palliative annoyance in the stern set of Hannah’s face. She even shrugged a little, a kind of wriggling that her friends undoubtedly called “cute.” She spoke in the unmistakable tone of the middle-class Negro.

“Hello, you.’ And big boy George! I heard you all walking about downstairs, so I came on up. I bin sittin’ by myself all evenin’. Even the gas went out. Here it’s New Year’s eve, I’m all dolled up, got an invite to a swell shebang sittin’ pretty on my dresserand my sweet daddy walks out on a case’. Say, wouldn’t that make you leave your happy home?”

George enjoyed it. He grinned sympathetically. Here was a congenial, Jazz-loving soul, and, child-like, he promptly shelved his present grievance. He wanted to show off. He wanted, a little pathetically, to blot out the hovering bitterness of Hannah in the gay camaraderie of Tillie.

He said eagerly, “Got some new records, Tillie.”

She was instantly delighted. “Yeh? Run ‘ern round the green.”

She settled herself in a comfortable chair and crossed her slim legs. Hannah went to the window in customary isolation.

George made a vain search of the cabinet. “Where’re them records, Hannah?” he asked.

“On the table edge,” she murmured fretfully.

He struggled to his feet and shuffled over to the table. “Lord,” he grumbled, “you ain’t undone ’em yet?”

“I’ve been too tired,” she answered wearily.

He and Tillie exchanged mocking glances. He sighed expressively, and Tillie snickered audibly. But their malicious little shafts fell short of the unheeding woman who was beating a sharp, impatient tattoo on the windowpane.

George swore softly.

“Whassa matter?” asked Tillie. “Knot?”

He jerked at it furiously. “This devilish string.”

“Will do,” she asserted companionably. “Got a knife?”

“Yep.” He fished in his pocket, produced it. “Here we go.” The razor-sharp knife split the twine. “All set.” He flung the knife, still open, on the table.

The raucous notes of a Jazz singer filled the room. The awful blare of a frenzied colored orchestra, the woman’s strident voice swelling, a great deal of “high brown baby” and “low down papa” to offend sensitive ears, and Tillie saying admiringly, “Ain’t that the monkey’s itch?”

From below came the faint sound of someone clumping, a heavy man stomping snow from his boots. Tillie sprang up, fluttered toward George.

“Jim, I’ll be Back. You come down with me, G. B., and maybe you c’ n coax him to come on up. I got a bottle of somethin’ good. We’ll watch the new year in and drink its health.”

George obediently followed after. “Not so worse. And there oughta be plenty o’ stuff in our icebox. Scare up a little somethin’ Hannah. We’ll be right back.”

As the door banged noisily, Hannah, with a dreadful rush of suppressed sobs, swiftly crossed the carpeted floor, cut short the fearful din of the record, and stood, for a trembling moment, with her hands pressed against her eyes.

Presently her sobs quieted, and she moaned a little, whimpering, too, like a fretful child. She began to walk restlessly up and down, whispering crazily to herself. Sometimes she beat her doubled fists against her head, and ugly words befouled her twisted lips. Sometimes she fell upon her knees; face buried in her out-flung arms, and cried, aloud to God.

Once, in her mad, sick circle of the room, she staggered against the table, and the hand that went out to steady her closed on a bit of sharp steel. For a moment she stood quite still. Then she opened her eyes, blinking them free of tears. She stared fixedly at the knife in her hand. She noted it for the first time: initialed, heavy, black, four blades, the open one broken off at the point. She ran her fingers along its edge. A drop of blood spurted and dripped from the tip of her finger. It fascinated her. She began to think: this is the tide of my life ebbing out. And suddenly she wanted to see it run swiftly. She wanted terribly to be drained dry of life. She wanted to feel the outgoing tide of existence.

She flung back her head. Her voice rang out in a strange, wild cry of freedom.

But in the instant when she would have freed her soul, darkness swirled down upon her. Wave upon wave of impenetrable blackness in a mad surge. The knife fell away. Her groping hands were like bits of aimless driftwood. She could not fight her way through to consciousness. She plunged deeply into the terrible vastness that roared about her cars.

And almost in awful mockery the bells burst into sound, ushering out the old, heralding the new: for Hannah, only a long, gray twelve months of pain-filled, sou

l-starved days.

As the last, loud note died away, Tillie burst into the room, followed by George and her husband, voluble in noisy badinage. Instantly she saw the prostrate figure of Hannah and uttered a piercing shriek of terror.

“Oh, my God! Jim!” she cried, and cowered fearfully, against the wall, peering through the lattice of her fingers.

George, too, stood quite still, a half-empty bottle clutched in his hand, his eyes bulging grotesquely, his mouth falling open, and his lips ashen. Instinctively although the knife lay hidden in the folds of her dress, he felt that she was dead. Her every prophetic, fevered word leaped to his suddenly sharpened brain. He wanted to run away and hide. It wasn’t fair of Hannah to be lying there mockingly dead. His mind raced ahead to the dreadful details of inquest and burial, and a great resentment welled in his heart. He began to hate the woman he thought lay dead.

Doctor Hill, puffing a little, bent expertly over Hannah. His eye caught the gleam of steel. Surreptitiously he pocketed the knife and sighed. He was a kindly, fat, little bald man with an exhaustless fund of sympathy. Immediately he had understood. That was the way with morbid, self-centered women like Hannah.

He raised himself. “Poor girl, she’s fainted. Help me with her, you all.”

When they had laid her on the couch, the gay, frayed, red couch with the ugly rent in the center Hannah’s nerve-tipped fingers had torn, Jim sent them into the kitchen.

“I want to talk to her alone. She’ll come around in a minute.”

He stood above her, looking down at her with incurious pity. The great black circles under her eyes enhanced the sad dark beauty of her face. He knew suddenly, with a tinge of pain, how different would have been her life, how wide the avenues of achievement, how eager the acclaiming crowd, how soft her bed of ease, had this gloriously golden woman been born white? But there was little bitterness in his thoughts. He did not resignedly accept the black man’s unequal struggle, but he philosophically foresaw the eventual crashing down of all unjust barriers.

Hannah stirred, moaned a little, opened her eyes, and in a quick flash of realization stifled a cry with her hand fiercely pressed to her lips. Doctor Hill bent over her, and suddenly she began to laugh, ending it dreadfully in a sob.

“Hello, Jim,” she said, “I’m not dead, am I? I wanted so badly to die.”

Weakly she tried to rise, but he forced her down with a gentle hand. “Lie quiet, Hannah,” he said.

Obediently she lay back on the cushion, and he sat beside her, letting her hot hand grip his own. She smiled a wistful, tragic, little smile.

“I had planned it all so nicely, Jim. George was to stumble upon my dead body-his own knife buried in my throat-and grovel beside me in fear and self-reproach. And Tillie, of course, would begin extolling my virtues, while you-Now it’s all spoilt!”

He released her hand and patted it gently. He got to his feet. “You must never do this again, Hannah.”

She shook her head like a willful child. “I shan’t promise.”

His near-sighted, kindly eyes bored into hers. “There is a reason why you must, my dear.”

For a long moment she stared questioningly at him, and the words of refutation that leaped to her lips died of despairing certainty at the answer in his eyes.

She rose, swaying, and steadied herself by her feverish grip on his arms. “No,” she walled, “no! No! No’!”

He put an arm about her. “Steady, dear.”

She jerked herself free, and flung herself on the couch, burying her stricken face in her hands.

Jim, I can’t! I can’t! Don’t you see how it is with me?”

He told her seriously, “You must be very careful, Hannah.”

Her eyes were tearless, wild. “But, Jim, you know-You’ve watched me. Jim! I hate my husband. I can’t breathe when he’s near. He-stifles me. I can’t go through with it. I can’t! Oh, why couldn’t I have died?”

He took both her hands in his and sat beside her, waiting until his and sat beside her, waiting until his quiet presence should soothe her. Finally she gave a great, quivering sigh and was still.

“Listen, Hannah,” he began, “you are nervous and distraught. After all, a natural state for a woman of your temperament. But you do not want to die. You want to live. Because you must, my dear. There is a life within you demanding birth. If you seek your life again, your child dies, too. I am quite sure you could not be a murderer.

“You must listen very closely and remember all I say. For with this new year-a new beginning, Hannah-you must see things clearly and rationally, and build your strength against your hour of delivery.”

Slowly she raised her eyes to his. She shook her head dumbly “There’s no way out. My hands are tied. Life itself has beaten me.”

“Hannah?”

“No. I understand Jim. I see.”

“Right,” he said, rising cheerfully. You just think it’s all over.” He crossed to the door and called, “George! Tillie! You all can come in now.”

They entered timorously, and Doctor Hill smiled reassuringly at them. He took his wife’s hand and led her to the outer door.

“Out with you and me, my dear. We’ll drink the health of the new year downstairs. Mrs. Byde has something very important to say to Mr. Byde. Night, G. B. Be very gentle with Hannah.”

George shut the door behind them and went to Hannah. He stood before her, embarrassed, mumbling inaudibly.

“There’s going to be a child,” she said dully.

She paled before the instant gleam in his eyes.

“You’re-glad?’

There was a swell of passion in his voice. “Hannah!” He caught her up in his arms.

“Don’t,” she cried, her hands a shield against him, “you’re-stifling me.”

He pressed his mouth to hers and awkwardly released her.

She brushed her hands across her lips; “You’ve been drinking. I can’t bear it.”

He was humble. “Just to steady myself. In the kitchen. Me and Tillie.”

She was suddenly almost sorry for him. “It’s all right, George. It doesn’t matter. It’s nothing.”

Timidly he put his hand on her shoulder. “You’re shivering. Lemme get you a shawl.”

“No.” She fought against hysteria. “I’m all right, George. It’s only that I’m tired.… tired.” She went unsteadily to her bedroom door, and her groping hand closed on the knob. “You-you’ll sleep on the couch tonight? I-I just want to be alone. Good night, George. I shall be all right. Good night.”

He stood alone, at a loss, his hands going out to the closed door in clumsy sympathy. He thought: I’ll play a piece while she’s gettin’ undressed. A little jazz’ll do her good.

He crossed to the phonograph, his shoes squeaking fearfully. There was something pathetic in his awkward attempt to walk lightly. He started the record where Hannah had cut it short; grinning delightedly as it began to whir.

The jazz notes burst on the air filled the narrow room. And the woman behind the closed door flung herself across the bed and laughed and laughed and laughed.

The Typewriter

Opportunity Magazine

JULY 1926

It occurred to him, as he eased past the bulging knees of an Irish wash lady and forced an apologetic passage down the aisle of the crowded car, that more than anything in all the world, he wanted not to go home.

He began to wish passionately that he had never been born, that he had never been married that he had never been the means of life’s coming into the world. He knew quite suddenly that he hated his flat and his family and his friends. And most of all, the incessant thing that would clatter until every nerve screamed aloud, and the words of the evening paper danced crazily before him, and the insane desire to crush and kill set his fingers twitching.

He shuffled down the street, an abject little man of fifty-odd years, in an ageless overcoat that flapped in the wind. He was cold, and he hated the North, and particularly Boston, and saw suddenly

a barefoot pickaninny sitting on a fence in the hot, Southern sun with a piece of steaming corn bread and a piece of fried salt pork in either grimy hand.

He was tired, and he wanted his supper, but he didn’t want the beans, and frankfurters, and light bread that Net would undoubtedly have. That Net had had every Monday night since that regrettable moment fifteen years before when he had told her-innocently-that such a supper tasted “right nice. Kinda change from what we always has.”

He mounted the four brick steps leading to his door and pulled at the bell, but there was no answering ring. It was broken again, and in a mental flash he saw himself with a multitude of tools and a box of matches shivering in the vestibule after supper. He began to pound lustily on the door and wondered vaguely if his hand would bleed if he smashed the glass. He hated the sight of blood. It sickened him.

Some one was running down the stairs. Daisy probably. Millie would be at that infernal thing, pounding, pounding.… He entered. The chill of the house swept him. His child was wrapped in a coat. She whispered solemnly, “Poppa, Miz Hicks an’ Miz Berry’s awful mad. They gointa move if they can’t get more heat. The furnace’s burnt out all day. Mama couldn’t fix it.”

He said hurriedly, “I’ll go right down. I’ll go right down.” He hoped Mrs. Hicks wouldn’t pull open her door and glare at him. She was large and domineering, and her husband was a bully. If her husband ever struck him, it would kill him. He hated life, but he didn’t want to die. He was afraid of God, and in his wildest flights of fancy couldn’t imagine himself an angel. He went softly down the stairs.

He began to shake the furnace fiercely. And he shook into it every wrong, mumbling softly under his breath. He began to think back over his uneventful years, and it came to him as rather a shock that he had never sworn in all his life. He wondered uneasily if he dared say “damn.” It was taken for granted that a man swore when he tended a stubborn furnace. And his strongest interjection was “Great balls of fire!”

The cellar began to warm, and he took off his inadequate overcoat that was streaked with dirt. Well, Net would have to clean that. He’d be damned-! It frightened him and thrilled him. He wanted suddenly to rush upstairs and tell Mrs. Hicks if she didn’t like the way he was running things, she could get out. But he heaped another shovel full of coal on the fire and sighed. He would never be able to get away from himself and the routine of years.

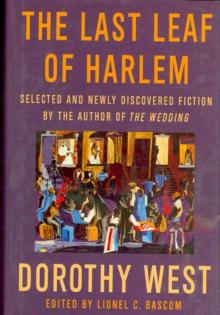

The Last Leaf of Harlem

The Last Leaf of Harlem